What is Sedentary Behavior?

Sedentary behavior has become a hot topic in modern health research. While it may be defined slightly differently across studies, the main idea is the same: it refers to activities that involve very little movement and low energy use.

In 2017, an international organization called the Sedentary Behaviour Research Network (SBRN) introduced a widely used modern definition of sedentary behavior:

Sedentary behavior is any waking behavior characterized by an energy expenditure ≤1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs), while in a sitting, reclining or lying posture.

Measuring Sedentary Behavior with METs

The definition of sedentary behavior is based on energy expenditure and is measured using METs (Metabolic Equivalent of Task) as a standard unit.What is MET?

1 MET represents the energy the body uses at rest — about 1 calorie per kilogram of body weight per hour. For example, for an adult male weighing 70 kg:

- Walking at 3 METs for one hour burns about 210 calories

- Sleeping for one hour burns about 70 calories, which is close to the body’s basal metabolic rate

- Jogging for one hour may burn around 560 calories

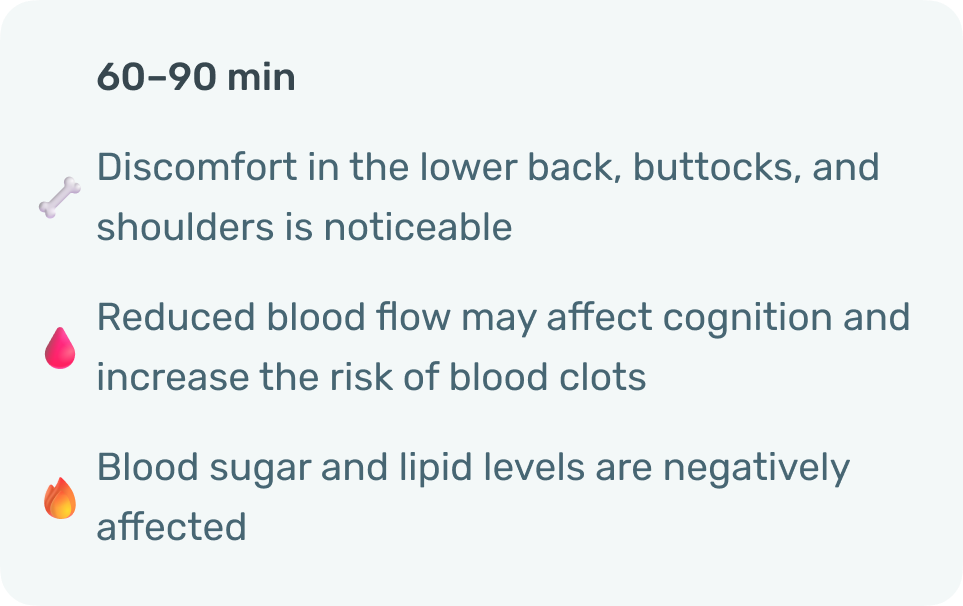

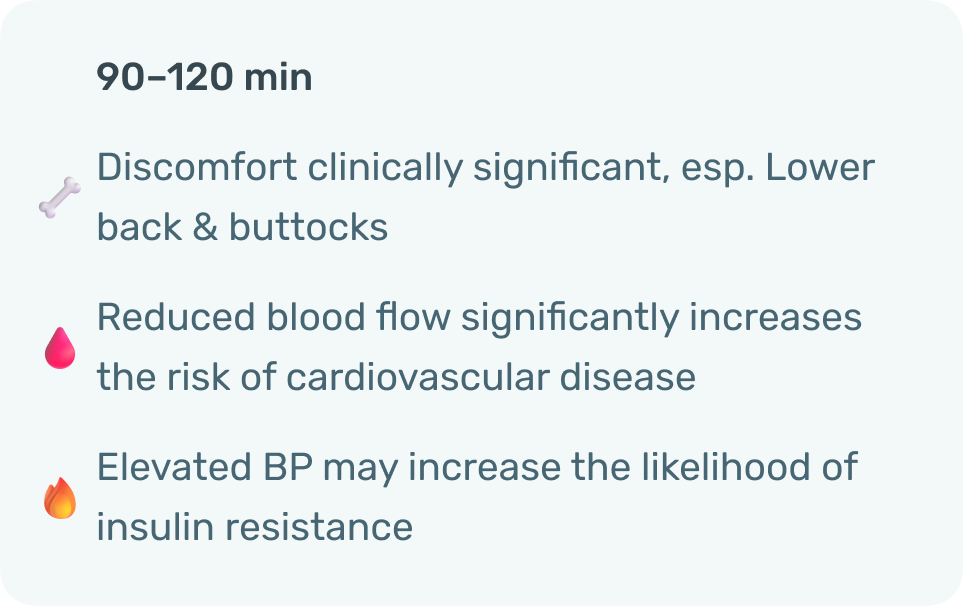

When the body stays in a low-energy state for long periods, muscle activity drops and overall metabolic demand decreases. Over time, this can raise the risk of several health issues, including insulin resistance, abdominal obesity, and deep vein thrombosis in the legs.

For this reason, long-term activity at or below 1.5 METs is defined as sedentary behavior. This definition has been widely accepted by major institutions, including the World Health Organization (WHO), Canadian Science Publishing, the University of Queensland, and The Lancet. It applies to many common daily activities such as watching TV, office work, reading, studying, and commuting.

Some studies slightly expand the range to under 2.0 METs, or use a range of 1.0–1.8 METs to account for minor posture changes. However, this broader range is not considered the strict or mainstream definition of sedentary behavior.

How Can You Tell if You’re Sitting Too Much?

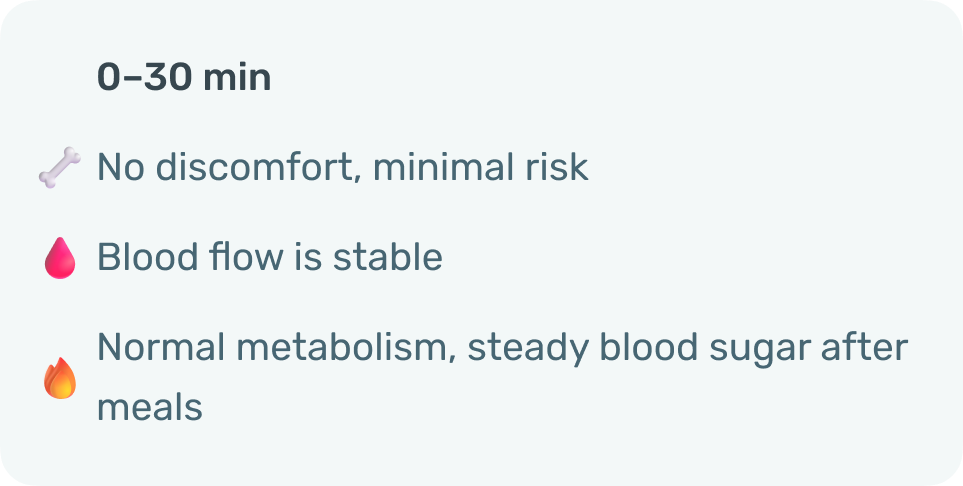

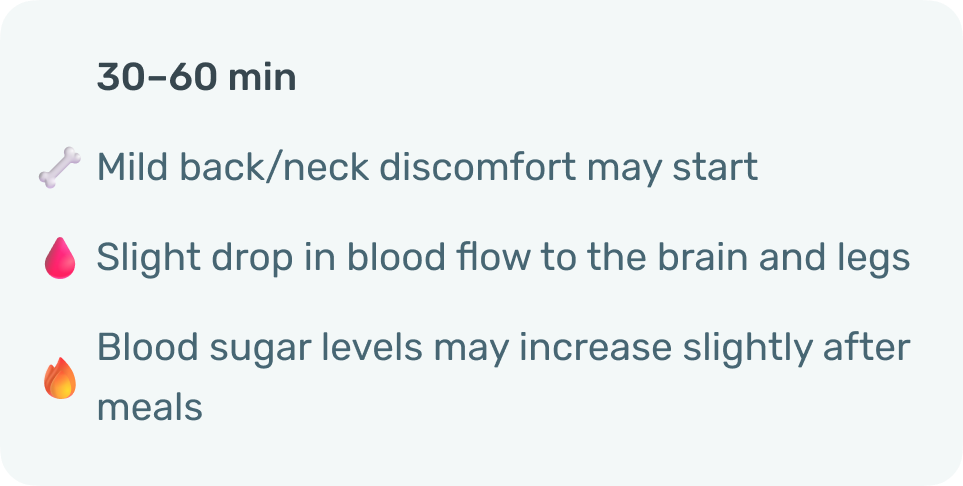

- Time guideline: Sitting for 30 minutes or more without getting up is generally considered sedentary behavior. Spending 8 hours or more sitting in a day is linked to greater health risks.

- Body signals: If you start noticing back pain, swollen legs, dizziness, or fatigue, these may be signs your body is reacting to too much sitting.

Everyday Sitting Habits and Their Risks

- Sitting at Work or School When your job or studies keep you in a chair for hours.

- Desk time: Computer work, classes, homework.

- Jobs that require sitting: Office staff, coders, writers, drivers.

- Sitting for Fun How we spend downtime in a seated, low-movement way.

- Screens: TV, gaming, scrolling on your phone.

- Other seated hobbies: Reading, board or card games.

- Daily Life & Travel The sitting we can’t always avoid in daily routines.

- Everyday moments: Eating, long meetings.

- On the move: Long drives, buses, trains, or flights.

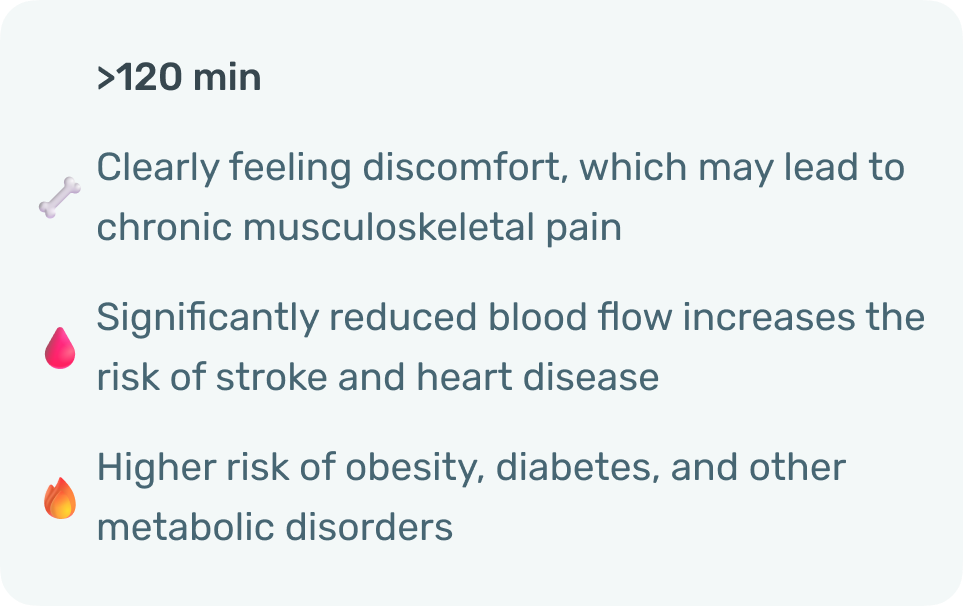

The longer you sit, the greater the physiological impact on your body.

How to Reduce the Harm from Sitting Too Long

- Here are some practical ways to minimize prolonged sitting:

- Stand up and move regularly: Use Relaxo to set reminders—get up and stretch or walk around for a few minutes every 30–60 minutes.

- Use work breaks wisely: Stand while taking calls or chatting with colleagues, and consider a standing desk if possible.

- Switch up leisure activities: Cut down on TV or phone time, and opt for walking, doing chores, or other light activities instead.

- Increase daily movement: Take the stairs instead of the elevator, and walk or bike for short trips whenever possible.

Sitting too long can harm your health—but simple changes make a difference. Stand up often, move during work or breaks, and swap some screen time for light activity.

References

Bull, F. C., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S., Borodulin, K., Buman, M. P., Cardon, G., Carty, C., Chaput, J. P., Chastin, S., Chou, R., Dempsey, P. C., DiPietro, L., Ekelund, U., Firth, J., Haskell, W. L., Haug, E., Lambert, E. V., Leitzmann, M., Loyen, A., … Willumsen, J. F. (2020). World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour - World Health Organization

GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. (2020). Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet, 396(10258), 1223–1249. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2.

Hamilton, M. T., Hamilton, D. G., & Zderic, T. W. (2007). Role of low energy expenditure and sitting in obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes, 56(11), 2655–2667. doi: 10.2337/db07-0882.

Patterson, R., McNamara, E., Tainio, M., de Sá, T. H., Smith, A. D., Sharp, S. J., Edwards, P., Woodcock, J., Brage, S., & Wijndaele, K. (2018). Sedentary behaviour and risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality, and incident type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose response meta-analysis. European Journal of Epidemiology, 33(9), 811–829. doi: 10.1007/s10654-018-0380-1.

Magnon, V., Plancher, G., Vallet, G. T., & Auxiette, C. (2018). Sedentary Behavior at Work and Cognitive Functioning: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 239. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00239.